Delving the depths of computing,

hoping not to get eaten by a wumpus

2020-09-07

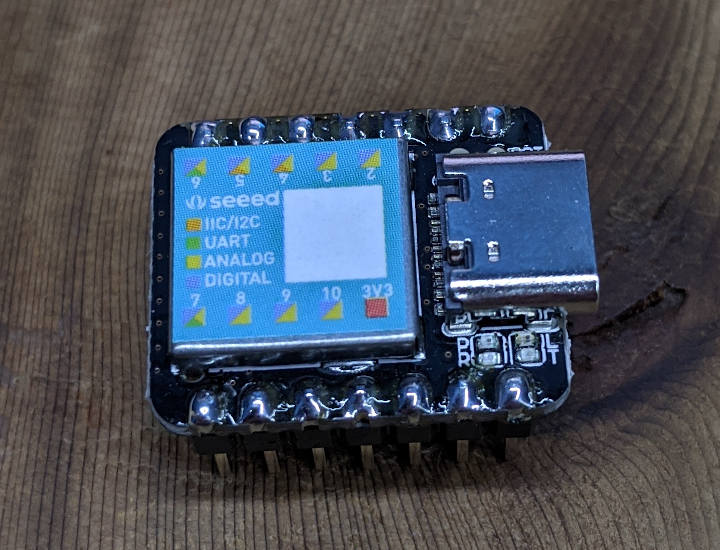

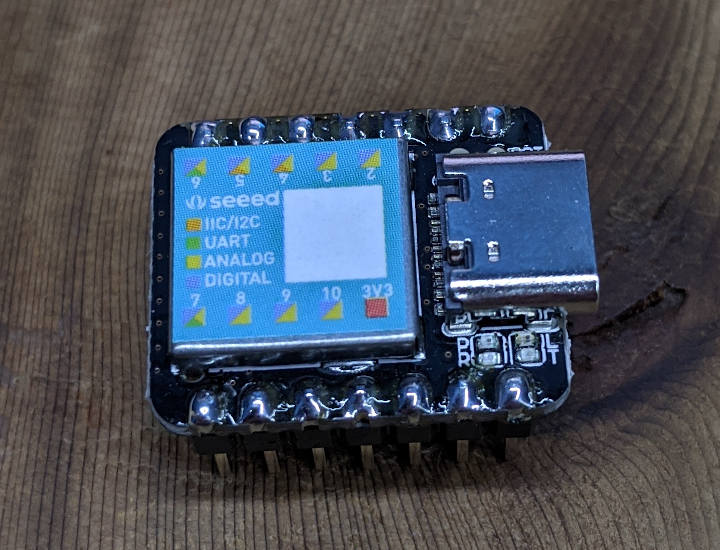

Seeed has been picking up in the maker community as a source of low cost alternatives to popular development boards. The Rock Pi S is an excellent competitor to the Raspberry Pi Zero, providing the quad core processor that the Pi Zero lacks. They have also released the Seeed XIAO, a small ARM-based microcontroller competing with Arduino or Teensy boards, and sent me units for this review.

The board is small but capable, with an ARM Cortex M0+ 32-bit processor running at 48MHz, 256KB of flash, and 32KB of SRAM. Programming is done through a USB-C port, which also powers the device. There are 14 pins, including one 5V output, one 3.3V output, and one ground. The rest are I/O pins, all of which are capable of digital GPIO, analog input, and PWM output. There's also a single DAC channel, plus I2C, SPI, and UART. Also included is a set of stickers that fit on the board's main chip and shows the basic pinout of the main 10 pins.

Shipping came directly from China, and took several months. I'm sure at least some of the delay was likely due to Coronavirus issues. Still, this isn't the first time I've seen Seeed be slow to ship. If you're interested in this product, I suggest ordering in advance.

Once it arrived, the board was easy to setup. Pin headers come in the package, but will need to be soldered. Their wiki page for the board was easy to follow, especially if you have previous experience with Arduino-based boards. Programming is done through the Arduino IDE, using a plugin that provides the right compiler environment and firmware flasher. Many new boards are preferring the free version of Microsoft Visual Studio with PlatformIO, but Seeed is choosing to stick with Arduino's IDE for this one.

The board can be tricky to get into programming mode. When uploading code, I often encountered an error like this in the IDE console (on a Windows machine):

processing.app.debug.RunnerException ... Caused by: processing.app.SerialException: Error touching serial port 'COM5'. ... Caused by: jssc.SerialPortException: Port name - COM5; Method name - openPort(); Exception type - Port busy.

Fixing this is done by double tapping the reset pad with a wire over to the pad right next to it. When it goes into bootloader mode correctly, Windows would often pop up a file manager for the device, as if a USB flash drive had been connected. This may also change the COM port, so be sure to check that before trying to upload again.

With that issue sorted, I uploaded the basic LED blinker example from Arduino, and it worked fine against the LED on the board itself. That shows the environment was sane and working.

I next turned my attention to a project I've had sitting on my shelf for a while: modifying an old fashioned oil lantern for a Neopixel. I received this lamp from a secret santa exchange party last year, and was told that while it had all the functional parts, it wasn't designed to take the heat of a real burning wick. So I picked up Adafruit's 7 Neopixel jewel, and combined it with NeoCandle, which would give a slight flickering effect. NeoCandle was designed for 8 Neopixels rather than 7, but commenting out the call to the eighth pixel worked fine.

Complicated libraries like this are often made for Arduino boards first, and everything else second, so I was bracing myself for a long debugging session to figure out compatibility. My worry was unnecessary, as the Adafruit Neopixel library worked without a hitch.

(White balance on my phone camera wasn't cooperating. The color of the light is more orange in person. It also has a very subtle flicker effect.)

At $4.90 each, this is a nice little board with a good feature set. It's cheaper than the Teensy LC, and in terms of processing power, more capable than Arduino Minis. Getting the binary uploaded can be janky, but to be fair, that's common on a lot of ARM-based microcontrollers. When a project doesn't need a lot of output pins, I would use this in place of a Teensy LC. Just watch for those shipping times.

2020-05-11

If you ask for advice on how to store passwords, you'll get some responses that are sensible enough. Don't roll your own crypto. Salted hashes aren't good enough against GPU attacks. Use a function with a configurable parameter that causes exponential growth in computation, like bcrypt. If the posters are real go-getters that day, they might even bring up timing attacks.

This is fine advice as far as it goes, but I think it's missing a big picture item: the advice has changed a number of times over the years, and we're probably not at the final answer yet. When people see the current standard advice, they tend to write systems that can't be easily changed. This is part of the reason why you still have companies using crypt() or unsalted MD5 for their passwords, approaches that are two or three generations of advice out of date. Someone has to flag it and then spend the effort needed for a migration. Having run such a migration myself, I've seen it reveal some thorny internal issues along the way.

Consider these situations:

- You run bcrypt. Is your cost parameter sufficient against attacks on current hardware? Can your servers afford to push it a little higher? What's your process for changing the cost parameter? Do you check in every year to see if it's still sufficient? If you changed it, would only new users receive the upgraded security, or does it upgrade users every time they login?

- You run scrypt. Tomorrow, news comes out showing that scrypt is irrevocably broken. What's your process for switching to something different? As above, would it only work for new users, or do old users get upgraded when they login?

- Your system is just plain out of date, running

crypt() or salted SHA1 or some such. How do you migrate to something else?

Castellated is an approach for Node.js, written in Typescript, that allows password storage to be easily migrated to new methods. Out of the box, it supports encoding in argon2, bcrypt, scrypt, and plaintext (which is there mostly to assist testing). A password encoded this way will look something like this:

ca571e-v1-bcrypt-10-$2b$10$wOWIkiks.tbbftwkJ81BNeuOtq631SzbsVOO7VAHf5ziH.edAAqJi

This stores the encryption type, its parameters, and the encoded string. We pull this string out of a database, check that the user's password matches, and then see if the encoding is the preferred type. Arguments (such as the cost parameter) are also checked. If these factors don't match up, then we reencode the password with the new preferred types and store the result. This means that every time a user logs in (meaning we have the plaintext password available to us), the system automatically switches over to the preferred type.

There is also a fallback method which will help in migrating existing systems.

All matching is done using a linear-time algorithm to prevent timing attacks.

It's all up on npm now.

2020-02-13

A common issue with makerspaces is letting people in the door. Members sign up and should have access immediately. Members leave and should have their access dropped just as fast. Given the popularity of the Raspberry Pi among makers, it makes sense to start there, but how do you handle the software end?

Doorbot.ts is a modular solution to this problem. It's split into three parts:

- A Reader takes input from some device. It could be a USB key reader, or a Wiegand RFID reader

- An Authenticator checks if the given input credentials are allowed

- An Activator does something if the input passes

A basic setup might read a keyfob from the reader, authenticate against an API held on a central server, and then (assuming everything checks out) activate a GPIO pin on the Raspberry Pi for 30 seconds. This pin could be connected to a solenoid or magnetic hold to unlock the door (usually with a MOSFET or relay, since the RPi can't drive the voltages for either of those).

The parts that interface to a Raspberry Pi (such as a Wiegand reader or activating a GPIO pin) are in a separate repository here: https://github.com/frezik/rpi-doorbot-ts

Security

The system can be compromised in quite a few ways. RFID tags can be copied. Cheap 10 digit keys can be brute forced. If you buy cheaply in bulk, there's a good chance those RFIDs are sequential or otherwise predictable. The Raspberry Pi can be compromised. The database can be compromised.

Which is not to say it's hopeless. That is, it's no more hopeless than what security you already have. An attacker can put a rock through any window. Physical locks can be picked, often without much skill at all. If you're like many makerspaces, you'll give a keyfob to anyone who shows up with membership dues, and you probably don't even check their ID.

So no, it's not the most secure system in the world, but it's also not the weakest point in the chain, either.

This isn't to say security should be ignored. Take basic precautions here, like using good passwords, and keeping the systems up to date.

Wiegand

Wiegand is a common protocol for RFID readers. There are cheap readers that work like a USB keyboard, "typing" the numbers of the fob. However, they're usually not built for outdoor mounting. There are cheap Wiegand options that are.

The protocol runs over two wires (plus power/ground). There is a Reader module in rpi-doorbot-ts for handling it directly. I don't recommend using it. The issue is that reading the data over GPIO pins means using tight timing, and doing this in Node.js is often unreliable. It often resulted in needing to scan fobs two or three times before getting a clean read.

Instead, you can use a C program who's only job is to read Wiegand, interpret the bits, and spit out the number. Doorbot.ts then has as Reader that can read a filehandle. So you launch the C program, pipe its stdout into the Reader, and there you go. From practical testing, this has been far more reliable in scanning fobs the first time.

Installing the System

I recommend creating a directory in your home dir on your Raspberry Pi:

$ mkdir doorbot-deployment

$ cd doorbot-deployment

And then create a basic package.json:

{

"name": "doorbot",

"version": "1.0.0",

"description": "",

"main": "index.js",

"scripts": {

"test": "echo \"Error: no test specified\" && exit 1"

},

"author": "",

"license": "ISC",

"dependencies": {

"@frezik/doorbot-ts": "^0.13.0",

"@frezik/rpi-doorbot-ts": "^0.6.0"

}

}

Be sure typescript is installed globally, and then install all the dependencies:

$ sudo npm install -g typescript

$ npm install

Next, make an index.ts to run the system:

import * as Doorbot from '../index';

const INPUT_FILE = "database.json";

let reader = new Doorbot.FHReader(

process.stdin

);

let auth = new Doorbot.JSONAuthenticator( INPUT_FILE );

let act = new Doorbot.DoNothingActivator( () => {

console.log( "Activate!" );

});

Doorbot.init_logger();

Doorbot.log.info( "Init" );

reader.setAuthenticator( auth );

auth.setActivator( act );

reader.init();

Doorbot.log.info( "Ready to read" );

reader

.run()

.then( () => {} );

This code creates a reader that works from STDIN, and authenticates against a JSON file, which would have entries like this:

{

"1234": true,

"5678": true,

"0123": false

}

It then hooks the reader, authenticator, and activator together and starts it running. You can type the key codes ("1234", "5678", etc.) in to get a response.

I'll be following up with some more advanced usages in future posts.

2019-08-26

TAP started as a simple way to test the Perl interpreter. It worked by outputting a test count on the first line, followed by a series of "ok" and "not ok" strings on subsequent lines. The hash character could be used for comments.

1..4

ok

ok

not ok # Better check if the frobniscator is working

ok

There's been some additions over the years, but a lot of output of individual tests still looks a lot like this. Multiple tests could be wrapped together with prove. Here's what it looks like to run that on Graphics::GVG:

$ prove -I lib t/*

t/001_load.t ............. ok

t/002_pod.t .............. ok

t/010_single_line.t ...... ok

t/020_many_lines.t ....... ok

t/030_circle.t ........... ok

t/040_rect.t ............. ok

t/050_color_variable.t ... ok

t/060_num_variable.t ..... ok

t/070_ellipse.t .......... ok

t/080_regular_polygon.t .. ok

t/090_int_variable.t ..... ok

t/100_glow_effect.t ...... ok

t/110_comments.t ......... ok

t/120_point.t ............ ok

t/130_include.t .......... skipped: Implement include files

t/140_include_vars.t ..... skipped: Implement include files

t/150_block_var.t ........ ok

t/160_poly_offset.t ...... ok

t/170_ast_to_string.t .... ok

t/180_two_parses.t ....... ok

t/190_meta.t ............. ok

t/200_renderer.t ......... ok

t/210_two_meta.t ......... ok

t/220_named_params.t ..... ok

t/230_renderer_class.t ... ok

All tests successful.

Files=25, Tests=91, 10 wallclock secs ( 0.10 usr 0.05 sys + 8.86 cusr 0.57 csys = 9.58 CPU)

Result: PASS

Since TAP is just text output, it's easy to implement libraries for other languages. With prove's --exec argument, we just pass an interpreter. Here's an example of a TypeScript project of mine:

$ prove --exec ts-node test/*

test/activator_do_nothing.ts ........ ok

test/activator_multi.ts ............. ok

test/authenticator_always_false.ts .. ok

test/authenticator_always.ts ........ ok

test/authenticator_multi_fails.ts ... ok

test/authenticator_multi.ts ......... ok

test/logger.ts ...................... ok

test/reader_fh.ts ................... ok

test/reader_mock.ts ................. ok

test/sanity.ts ...................... ok

All tests successful.

Files=10, Tests=12, 17 wallclock secs ( 0.05 usr 0.01 sys + 30.40 cusr 1.16 csys = 31.62 CPU)

Result: PASS

Although the TAP package for JavaScript has a nice little runner all its own, which includes an automatic coverage report:

$ node_modules/.bin/tap --ts test/**/*.ts

PASS test/activator_do_nothing.ts 1 OK 5s

PASS test/authenticator_always_false.ts 1 OK 5s

PASS test/activator_multi.ts 2 OK 5s

PASS test/authenticator_always.ts 1 OK 5s

PASS test/authenticator_multi_fails.ts 1 OK 5s

PASS test/authenticator_multi.ts 1 OK 5s

PASS test/logger.ts 1 OK 5s

PASS test/reader_fh.ts 2 OK 5s

PASS test/sanity.ts 1 OK 3s

PASS test/reader_mock.ts 1 OK 3s

🌈 SUMMARY RESULTS 🌈

Suites: 10 passed, 10 of 10 completed

Asserts: 12 passed, of 12

Time: 14s

--------------------------|----------|----------|----------|----------|-------------------|

File | % Stmts | % Branch | % Funcs | % Lines | Uncovered Line #s |

--------------------------|----------|----------|----------|----------|-------------------|

All files | 93.04 | 78.57 | 82.86 | 93.33 | |

doorbot.ts | 100 | 80 | 100 | 100 | |

index.ts | 100 | 80 | 100 | 100 | 26 |

doorbot.ts/src | 91.4 | 77.78 | 81.82 | 92.31 | |

activator_do_nothing.ts | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | |

activator_multi.ts | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | |

authenticator_always.ts | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | |

authenticator_multi.ts | 100 | 80 | 100 | 100 | 22 |

read_data.ts | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | |

reader.ts | 28.57 | 100 | 25 | 33.33 | 39,40,41,44 |

reader_fh.ts | 81.25 | 0 | 50 | 81.25 | 43,53,54 |

reader_mock.ts | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | |

--------------------------|----------|----------|----------|----------|-------------------|

Which, of course, can be dropped into the scripts -> test section of your package.json.

There's a feature of TAP that's been falling out of use in recent years, even in Perl, and that's test counts. Modern TAP allows you to put the test counts at the end, which can be done in Test::More by calling done_testing(). In the tap module for Node.js, you can simply not set a test count at all and it does it for you. Here's an example of that with a sanity test, which just makes sure we can run the test suite at all:

import * as tap from 'tap';

import * as doorbot from '../index';

tap.pass( "Things basically work" );

Avoiding a test count seems to be the trend in Perl modules these days. After all, automated test libraries in other languages don't have anything similar, and they seem to get by fine. If the test fails in the middle, that can be detected by a non-zero exit code. It's always felt like annoying bookkeeping, so why bother?

For simple tests like the above, I think that's fine. Failing with a non-zero exit code has worked reliably for me in the past.

However, there's one place where I think TAP had the right idea way back in 1988: event driven or otherwise asynchronous code. Systems like this have been popping up in Perl over the years, but naturally, it's Node.js that has built an entire ecosystem around the concept. Here's one of my tests that uses a callback system:

import * as tap from 'tap';

import * as doorbot from '../index';

import * as os from 'os';

doorbot.init_logger( os.tmpdir() + "/doorbot_test.log" );

tap.plan( 1 );

const always = new doorbot.AlwaysAuthenticator();

const act = new doorbot.DoNothingActivator( () => {

tap.pass( "Callback made" );

});

always.setActivator( act );

const data = new doorbot.ReadData( "foo" );

const auth_promise = always.authenticate( data );

auth_promise.then( (res) => {} );

If the callback to run tap.pass() never gets hit, this test will fail. If you had removed the call to tap.plan( 1 ) towards the start, it would pass as long as it compiles and doesn't otherwise hit a fatal error. Which is a pretty big thing to miss, since the callback is critical to the functionality of this particular module. Even if I knew it worked now, it might not in regression testing later.

Most (all?) other automated test frameworks around JavaScript have this problem. Sometimes, you can get around it by writing in clever ways, but it is far too easy to write test code that can erroneously declare success. Besides, shouldn't your tests be written in the most obvious, straightforward way? TAP had the answer decades ago.

2019-01-15

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EtxFP93h6ss

2018-11-26

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qdT9e5eCBYY

2018-10-28

Some years ago, I wrote a little top-down shooter in Perl. It was not a good game, and was never released, but I learned a lot making it. One problem I encountered was collision detection. Checking every object for collisions against every other object is not feasible past a small size. Especially in pure Perl, since this is a straight numeric problem, but it's still a struggle for C to do it.

We have faster processors now, so the number of objects you can throw in there has increased a lot. Still, it'd be better to have a faster algorithm than brute force. The typical choice is to use a binary partition tree to split up Axis Aligned Bounding Boxes. This lets you do very fast collision detection even with gigantic lists of objects. I won't go into detail here, as there's an excellent blog post that already goes into it:

https://www.azurefromthetrenches.com/introductory-guide-to-aabb-tree-collision-detection/

Most likely, you would use this to quickly prune the list of possible collisions ("broad phase"), and then use more expensive techniques to get pixel-perfect ("narrow phase").

This is what's implemented in Game::Collisions v0.1. Here's some benchmarks comparing the tree-based technique to brute force (running on a modest laptop CPU, an Intel i7-6500U):

Running tree-based benchmark

Ran 1000 objects 6000 times in 1.845779 sec

3250660.01942811 objects/sec

54177.6669904685 per frame @60 fps

Running brute force benchmark

Ran 1000 objects 6000 times in 6.201839 sec

967454.975854742 objects/sec

16124.249597579 per frame @60 fps

This creates a tree of 1000 leaf objects and then gets all the collisions for a specific AABB. As the number of AABBs increases, we would expect brute force to go up linearly, but the tree method to go up logarithmically, so these numbers will get further apart as the tree grows.

2018-09-26

The eBook was released on Monday, and coupon codes to backers were sent out on Tuesday. After a glitch with the first batch of coupons, the second batch was sent out and seems to be all good.

The book assumes you have some knowledge of Perl, but little knowledge of electronics or the Raspberry Pi. It goes through the tools you'll need, walks through the basic setup of the RPi, and then gets into programming. Starting out with blinking an LED, it later gets into facial recognition and controlling a garage door over the web.

I had hoped that we were releasing on time, and completely forgot that we originally promised a date in August, not September. Oops. Well, a month late still isn't bad for a crowdfunded project.

Expecting to get some of the coupon codes caught in spam filters. That's just the nature of sending out a lot of emails that say "here's your free coupon code!". Spammers ruin the Internet. Backers, if you don't see your code at this point, check your spam filter, and then message the campaign directly if you still don't see it.

This is the first time I've done a crowdfunded campaign that worked out. It's a modest start--not about to retire on that money--but it's good to have a track record. I tend to be picky about projects I back, and an established track record from the campaign members is one of the things I look at. I expect a lot of other people do the same. I'll likely have other projects in the future, and this is a good stepping stone.

2018-09-04

A while back, I built a DIY sous vide cooker. It's gone through a major revision since the original. My current one uses power outlets to connect the teacup heaters, rather than hard wiring them in. I'm in the midst of making another big change to it, which is to use an ESP8266 with custom programming, rather than an off the shelf PID controller, and also to use a different temperature probe.

Which brings me to this post. The original instructions used a k-type thermocouple, probably because it's cheap and easily available. After some research, I think the accuracy range of the k-type thermocouple is unacceptable for sous vide.

The accuracy of a k-type thermocouple, for the temperature range we care about for sous vide, is ±2.2C. Now, the FDA recommends that food never be stored between 5C and 54.5C for more than four hours. That means if you're cooking beef at a medium-rare temperature of 56.5C, a k-type thermocouple could be below the safe temperature.

It's also worth mentioning that the k-type thermocouple's temperature range is far beyond what we need for sous vide. We want something that will be accurate inside 50C and 100C. The tighter range of the t-type thermocouple is still more than we need, and its accuracy (for what we care about) would be ±1.0C.

We may be able to do better still. Resistance Temperature Detectors (RTD) probes are more accurate still. A probe with Class-A accuracy would be ±0.35 or less. It may also be cheaper, as you avoid the need for an amplifier chip, which you need with a thermocouple to convert its microvolts into something readable on normal electronics. RTDs just need something that can read resistance.

Which would be no problem on an Arduino with two ADC channels. You need the second one to read a resistor with a known value and then do some math to compare. Unfortunately, the ESP8266 (needed for some of the wireless features I want) only has one ADC channel. There's some ways to fix that, but they involve some extra hardware. Might end up being a wash in terms of price and complexity. Still, I think it's worth it for the extra accuracy.

Edit: doing it with a single ADC is possible with a voltage divider, which just needs a resistor with a known value. Cheap and easy.

2018-04-07

Device::WebIO::RaspberryPi 0.900 has been released. The big changes are to change the backend from HiPi to RPi::WiringPi, as well as put in a new input event system based on AnyEvent. There's also some slight updates to interrupt handling in Device::WebIO in version 0.022 to support this.

It works by having a condvar with a subref. You can get the pin number and its value out of $cv->recv:

use v5.14;

use Device::WebIO;

use Device::WebIO::RaspberryPi;

use AnyEvent;

use constant INPUT_PIN => 2;

my $rpi = Device::WebIO::RaspberryPi->new;

my $webio = Device::WebIO->new;

$webio->register( 'rpi', $rpi );

my $input_cv = AnyEvent->condvar;

$input_cv->cb( sub {

my ($cv) = @_;

my ($pin, $setting) = $cv->recv;

say "Pin $pin set to $setting";

});

$webio->set_anyevent_condvar( 'rpi', INPUT_PIN, $input_cv );

say "Waiting for input";

my $cv = AE::cv;

$cv->recv;

This is one part of a series of updates to support an upcoming Device::WebIO::MQTT. The original versions of the Device::WebIO family were meant to an HTTP interface (like the one in Device::WebIO::Dancer). Where HTTP pulls data, MQTT is push. The new AnyEvent system should integrate easily with AnyEvent::MQTT.

MQTT is also part of our stretch goals for the Raspberry Pi Perl eBook. Don't worry though--I'll be working on Device::WebIO::MQTT regardless of the funding level on the book.

← Prev

Next →

Copyright © 2025 Timm Murray

CC BY-NC

Email: tmurray@wumpus-cave.net

Opinions expressed are solely my own and do not express the views or opinions

of my employer.